Sierra Los Pinos

You are here

Seeking the Natural and the Undisturbed

A Plan to Preserve

A public meeting called in Jemez Springs by the Santa Fe National Forest (SFNF) threatened to be an angry affair with claims by local residents that SFNF planned to permanently shut down almost the entire Jemez Ranger District.

The meeting began with facilitators and National Forest staff appealing to the audience to conduct discussions with respect for one another and for each other's views. This affected the meeting, which was conducted in good spirit, and allowed residents to learn about and give input on the land management plan for the Jemez Ranger District, which is evaluating if any parts of the Forest are suitable for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System.

The turnout was large, practically filling the spaces by the long tables in Madonna Hall in Jemez Springs. This attendance was partly driven by the alarming notices warning of the dangers contained in the plan that were posted around the Jemez Valley on flyers and on social media online. The fears expressed in the notices were discussed and largely laid to rest for most of the participants, but the event organizers were grateful for the flyers, since they helped boost attendamce.

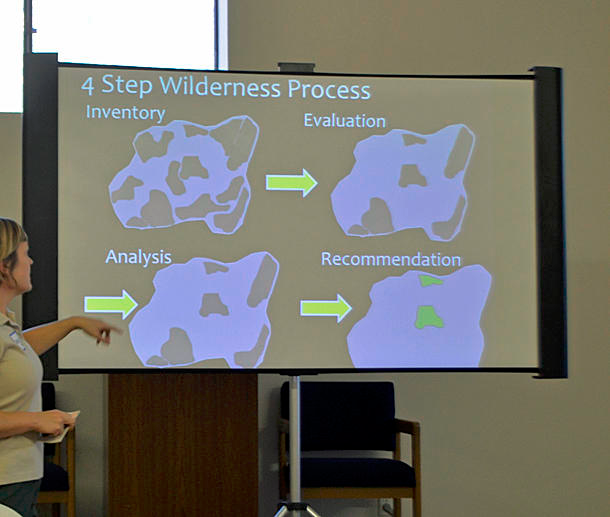

The meeting began by describing the Forest Plan Revision Process as a long overdue attempt to identify and evaluate areas which have wilderness characteristics, and then to permanently protect these most natural and undisturbed places. The process is divided into four steps: inventory, evaluation, analysis and recommendation; each step tied to first securing and then considering public input and scientific appraisal.

The first step, inventory, was cause for alarm for many observers since it included for consideration as wilderness very large sections of the Jemez Ranger District. However, it was made clear at the outset that large swathes of these areas clearly did not meet the criteria for wilderness through being dominated by well established roads, manmade structures, traditional use, such as grazing, or through being too small with proximity to areas with other uses, for effective management. They were included in the inventory largely for not having very obvious features eliminating them.

The second step, evaluation, after some of the most obvious non-wilderness areas have been winnowed out from the inventory, applies to sites the criteria for wilderness in detail, and is the current stage of the Forest Plan Revision Process. Discussing this step was where public input became very interesting, since many in the audience were intimately familiar with unique locations and little known aspects of the forest. Some, Jemez and Zia and other Native people, represented communities which have traditional and cultural activities that connected them to these landscapes long before wilderness preservation became an issue. Others were able to describe natural and non-native plant communities, and wildlife commonly occurring in those areas, and others yet were familiar with the history and impact of human intervention in what might appear to be, at a casual glance, an undisturbed space.

The criteria for wilderness, applied by the Forest Service, appear to be quite strict. The most obvious is a definition of a place which is natural, undisturbed and provides solitude. So, at that above mentioned casual glance, much of the high country in our area appears to fit the wilderness category, while at a closer glance, so much of it is rife with departures from naturalness.

There lurk in the woods firm old roads that show no sign of going away, mines, pipelines, troughs, water tanks and corrals, powerlines, acres of tree stumps from forest thinning and complete landscape alterations for watershed management. Here you can find a conflict between the Forest Plan Revision and the Southwest Jemez Mountains Landscape Restoration (SWJMLR). While the former looks for natural landscapes, the SWJMLR is focused on restoring landscapes to healthier conditions, which can actually involve improving roads in thinning areas, not to mention the actual thinning of areas of dense growth that can be prone to catastrophic crowntop fires.

These can be considered essential actions, but hardly acts of nature. At the same time, fierce crowntop fires that not only destroy all life on the ground, but kill the soil itself, are the result of many years of vigorous fire suppression. A landscape of charred tree stumps is a wilderness of sorts, but not the kind the Restoration Plan is looking for.

It is worth noting though, that certain activities, such as mining or grazing, and of course cultural or traditional uses, if they legally exist at the time of the area's designation as a wilderness, are allowed to continue at these locations. They need to be unobtrusive, their imprint unnoticeable and dominated by natural forces, allowing for a person to experience separation from civilization and connection to nature.

The next, third step in the Restoration Plan, will take into consideration additional issues that might be connected to locations proposed as wilderness areas. At this stage no new areas are being considered, but the proposed ones are studied to see if wilderness is the best classification for them.

In the final, fourth step, if any areas are recommended, they will go to the U.S. Congress for designation. Since this is a lengthy process, likely to take years, the recommended areas will be protected to retain wilderness characteristics during the wait.